by Seán Hudson

In the spirit of the season, let’s look at how horror works. I think we can isolate three images that recur in horror films, each creating affect in its own way. By “image”, I don’t mean a specific delineation that can only be static and visual, but a general delineating type that includes movement and affect. As a disclaimer, I’ll say that any systematising on my part aims not to provide a finalised explanation of how stuff works, but to provoke further thought on the matter at hand – that the following ideas lack rigorous analysis and a dedicated methodological origin can be foreshadowed with the knowledge that I identify precisely three images of fear on the basis that Three is the Magic Number, and it’s that playful time of year when illogical ritualism seems as good a reason as any to go about one’s thoughts.

First image: repulsion. The one that the popular consciousness most readily associates with the horror film. This is the reason that people will hide behind their hands, or if they’re nimble behind their sofas – what we experience is a fear of the image itself, testified to by the fact that we try and protect ourselves from the threat by not looking. This image has enjoyed a recent notoriety in the emergence of the “torture porn” sub-genre, which is all about the threat/promise of showing us what most people would not want to see. Films like Hostel (2005), in which we are forced to watch characters strapped to chairs undergo all manner of painful bodily disfigurement, while we are stuck in our chairs at home daring each other to watch. This voyeuristic image creates an interesting oppositional effect: it’s spectator versus image, the spectator taking on the role of hero and the image taking on the role of monstrous Other, only to be overcome by braving your way through the whole film, surviving in the face of so much death. This image therefore reaffirms the Self/Other binary by setting the viewer against itself.

Second image: morbidity. A scene from Beetlejuice (1988) springs to mind: told they must make themselves appear frightening, the dead protagonists begin experimenting with their bodies, stretching and contorting themselves into delightfully grotesque shapes. Often over-lapping with the first image, this image is defined by curiosity and playfulness. There is a certain degree of fascination in seeing grotesque or simply spooky figurations, whether it’s the graphic re-imagining of what bodies look like or the grim contours of an uninhabited building at night. The morbid image, with its natural alliance to comedy and the carnivalesque, often vies with the repulsive image, resulting in scenes that you may find horrifying while your friend giggles manically and vice versa. It’s often the mark of a good film when it manages to retain control over the production of these images, through pacing, atmosphere, etc. Evil Dead II (1987) is perhaps the classic in being able to build fear that erupts into laughter, providing an unpredictable rhythm of tension and relief. Even Hostel: Part II (2007) manages to admirably construct the shift from repulsive horror to “black comedy” in its final scene of a group of children playing football with a severed head. Of course, the filmmakers only ever have so much control over what is produced for an audience – many people go to even the most repulsive horror films not to be scared, but to laugh: the first image is repressed in favour of the second, either because the viewer is genuinely desensitised to the repulsive affect and experiences primarily the morbid image, or as a defence mechanism to avoid the terror that the first image might provoke. One friend of mine had the particularly annoying habit of turning to me and saying “Boo!” in a jokey voice, even waving his fingers in the air, when the tension of a horror film had reached its peak – what is presented as ludicrous cannot be terrifying, and so rather than being challenged by an Other, the Self plays with it, pokes fun at it, perhaps even finds it endearing. Just think of the reappropriation of horror figures like Dracula and Godzilla as familiar pop icons – a morbid fascination leading to mass habitualisation via media and marketing strategies has defanged and made fluffy some of cinema’s most terrifying monsters.

Third image: intensiveness. We’ve covered fear of the image, but now we move on to fear as the image. In my previous post, I outlined my belief that film has the fundamental power to disturb us by challenging the categories that we impose on the world. This third image occurs when that power of film is exploited to produce an affect that disintegrates the Self rather than challenge it with an Other – the binary dissolves when we experience pure affect. Horror is embodied on the screen rather than merely represented. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974), for example, is a showcase for techniques that form this third image of fear: sound, framing, colour, and elaborate set pieces ensure that fear is a result of captivating form rather than content.

Third image: intensiveness. We’ve covered fear of the image, but now we move on to fear as the image. In my previous post, I outlined my belief that film has the fundamental power to disturb us by challenging the categories that we impose on the world. This third image occurs when that power of film is exploited to produce an affect that disintegrates the Self rather than challenge it with an Other – the binary dissolves when we experience pure affect. Horror is embodied on the screen rather than merely represented. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974), for example, is a showcase for techniques that form this third image of fear: sound, framing, colour, and elaborate set pieces ensure that fear is a result of captivating form rather than content.

One of the many points of interest concerning this third image is how it poses a problem for censors. Consider the dilemma of the BBFC (British Board of Film Classification) when faced with The Texas Chain Saw Massacre:

“It was noted at the time that the film relied for its effect upon creating an atmosphere of madness, threat and impeding [sic] violence, whilst shying away from showing much in the way of explicit detail. This made it very difficult for the BBFC to cut the film into what might be regarded as an acceptable version since there were few moments of explicit violence that could be removed. Even if these elements were cut, it did nothing to alter the disturbing ‘tone’ of the film.” (BBFC)

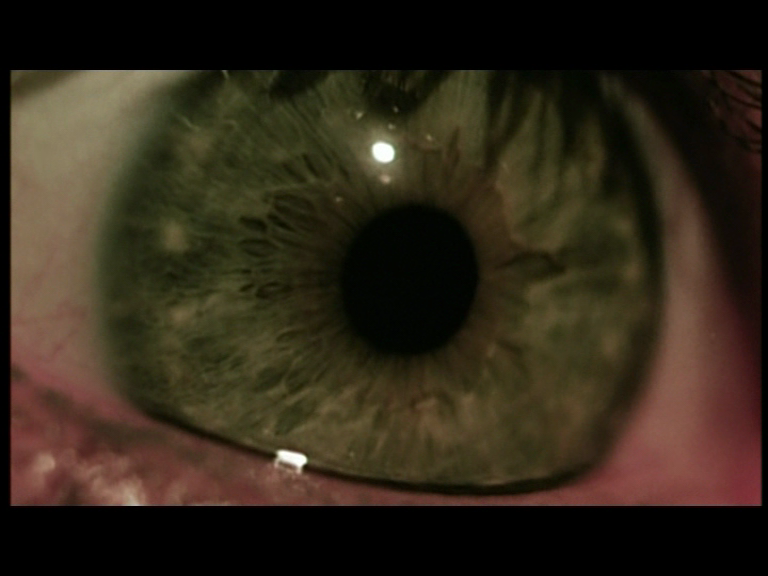

This disturbing tone meant that Britain didn’t get a general release on video till 1999. If the film had relied on the production of repulsive images, it would have been an easy case of simply removing those images – like how, when we were small, I used to protectively cover my little sister’s eyes during the scary bits of films, censorship being the obvious duty of a big brother. But what to do when the “explicit detail” that engenders fear is a cluster of yellow sunflowers fragmenting the characters in the background as we hear a generator buzzing ominously in the distance, or the repeated extreme close-up of a blue iris? That last example must be one of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre’s most vicious assaults on the viewer, cutting to different angles over and over as we hear the relentless screaming of the fearful protagonist, forced to watch her terror embodied in this strange blue disc, intimately close and sliced again and again by jump cuts – no one’s going to leave the cinema scared of sunflowers and irises, and yet the scariness is there.

Critics as well as censors have been baffled by The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. Roger Ebert, giving it two stars, made this telling comment in his review at the time of its release:

“It’s also without any apparent purpose, unless the creation of disgust and fright is a purpose. And yet in its own way, the movie is some kind of weird, off-the-wall achievement. I can’t imagine why anyone would want to make a movie like this, and yet it’s well-made, well-acted, and all too effective.” (Ebert 1974)

The creation of fear as an affect is contrasted against the idea of a successful and well-made film by the “and yet”: Ebert recognised two aspects and set them in opposition to each other, rather than identifying them as two ways of saying the same thing. While he inverts it, Dave Kehr establishes the same dichotomy when he tells us that “The picture gets to you more through its intensity than its craft” (Kehr). Let’s think about how such intensity is crafted.

What we have in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is the production of unintelligible signs – pots, pans, and a pierced clock all dangling from a tree; the sight of skeletons artfully reassembled as furniture as we hear the relentless clucking of a caged chicken – these images may be evocative, but they have no currency in our world, as they don’t signify horror, and so escape censorship. Yet in the world of the film, they’re central: “Everything means something, I guess,” says our hero Sally in response to whether she believes in horoscopes. Like Alice lost in Wonderland, she and the viewer encounter signs which indicate an internal logic that is nonetheless alien to us – it’s this production of signs without knowable meaning that truly disturbs us. “I just can’t take no pleasure in killing,” says one of Sally’s torturers, a frown on his face. “Just some things you gotta do – don’t mean you have to like it.” Despite the fact that he giggles sadistically through a lot of Sally’s suffering, this character’s statement holds the key to how the horror of this film works: madness is not so much an Other, but a set of invisible rules. The world itself is mad, and the Self, with all its prior memories and habits, is useless in this new place. “I’ll do anything,” Sally says at one point, trying to force a smile, and the viewer instantly interprets that she is offering sexuality in exchange for her life, even as we recognise that her offer is invalid here, as it relies on assumptions about why men kidnap women applicable to our world only: it holds no currency in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. Conversely, intensive images are generated by the codes that are encrypted in our world, signs that have no signifieds.

What we have in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is the production of unintelligible signs – pots, pans, and a pierced clock all dangling from a tree; the sight of skeletons artfully reassembled as furniture as we hear the relentless clucking of a caged chicken – these images may be evocative, but they have no currency in our world, as they don’t signify horror, and so escape censorship. Yet in the world of the film, they’re central: “Everything means something, I guess,” says our hero Sally in response to whether she believes in horoscopes. Like Alice lost in Wonderland, she and the viewer encounter signs which indicate an internal logic that is nonetheless alien to us – it’s this production of signs without knowable meaning that truly disturbs us. “I just can’t take no pleasure in killing,” says one of Sally’s torturers, a frown on his face. “Just some things you gotta do – don’t mean you have to like it.” Despite the fact that he giggles sadistically through a lot of Sally’s suffering, this character’s statement holds the key to how the horror of this film works: madness is not so much an Other, but a set of invisible rules. The world itself is mad, and the Self, with all its prior memories and habits, is useless in this new place. “I’ll do anything,” Sally says at one point, trying to force a smile, and the viewer instantly interprets that she is offering sexuality in exchange for her life, even as we recognise that her offer is invalid here, as it relies on assumptions about why men kidnap women applicable to our world only: it holds no currency in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. Conversely, intensive images are generated by the codes that are encrypted in our world, signs that have no signifieds.

Despite the obscurity of its affective signs, many critics shared the BBFC’s judgement that the film’s “intention seemed to be to invite the audience to revel in a vulnerable woman’s distress” (BBFC). It is interesting that a film should be seen as an invitation to sadism when it consistently assaults the audience with violent images (and by violent I mean both the shot of meat-hooks and that of afore-mentioned sunflowers). The prefiguration of the audience as a man watching an objectified woman speaks more about prevailing cultural attitudes than the experience of watching the film itself, as Carol J. Clover asserts in her lovely book Men, Women, and Chainsaws. That masochistic identification is necessary on some level for a film to be scary may seem blindingly obvious, but the idea that horror is more about vulnerability than aggression is still largely absent in popular film criticism and discourse.

Lest what began as an aesthetic inquiry transform further into a fan-boy’s gushing over one of his favourite films, I’ll bring in some Deleuze. It seems to me that the reason horror is still coded in terms of aggression rather than vulnerability or submission is linked to a general trajectory for what images we will be most open to. Deleuze tells us that in every aspect of life we enter into apprenticeships to signs, and these apprenticeships have three progressive stages: to interpret the sign as a property of its object, then to interpret the sign as part of our own subjective gaze, and finally to interpret the sign as an emitter of a non-generalisable essence, neither fully subjective nor objective. Although I previously asserted the whimsical rationale behind choosing precisely three images of fear, I wonder if perhaps I was influenced by a subconscious Deleuzian diagram – whatever the case, I now can’t help seeing these three images as stages in an apprenticeship: the repulsive image locates fear in the object, the morbid image considers fear as a subversion of the subject, and the intensive image does away with subject and object (Self and Other) in the wake of pure sensation. So although all three images are available to everyone, if most of us are more receptive to the first type, it’s no wonder it dominates the media representation of horror films. Even an advance to the second type would only complicate the Self-Other binary rather than overcome it. Which is not to say that these two images are inferior to the intensive image – there’s a definite hierarchy here, but each level has its own worth, in my opinion.

Lest what began as an aesthetic inquiry transform further into a fan-boy’s gushing over one of his favourite films, I’ll bring in some Deleuze. It seems to me that the reason horror is still coded in terms of aggression rather than vulnerability or submission is linked to a general trajectory for what images we will be most open to. Deleuze tells us that in every aspect of life we enter into apprenticeships to signs, and these apprenticeships have three progressive stages: to interpret the sign as a property of its object, then to interpret the sign as part of our own subjective gaze, and finally to interpret the sign as an emitter of a non-generalisable essence, neither fully subjective nor objective. Although I previously asserted the whimsical rationale behind choosing precisely three images of fear, I wonder if perhaps I was influenced by a subconscious Deleuzian diagram – whatever the case, I now can’t help seeing these three images as stages in an apprenticeship: the repulsive image locates fear in the object, the morbid image considers fear as a subversion of the subject, and the intensive image does away with subject and object (Self and Other) in the wake of pure sensation. So although all three images are available to everyone, if most of us are more receptive to the first type, it’s no wonder it dominates the media representation of horror films. Even an advance to the second type would only complicate the Self-Other binary rather than overcome it. Which is not to say that these two images are inferior to the intensive image – there’s a definite hierarchy here, but each level has its own worth, in my opinion.

Anyway, that we resist the pure affect of images is clear. The final shot of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre shows us Leatherface, the infamous chainsaw-wielder, cutting at the air and dancing in circles to the revving of his machine as the setting sun intensifies the striking sepia tones of the image. Synopses tend to describe this image as one of frustration – the baddie has been foiled, after all. But in fact there’s no obvious meaning behind the image: spinning on tip-toes in a ballet-like posture is not a sign that points to an easily identifiable emotion. The image doesn’t ask us to refer to the narrative in order to interpret its vivid form. Instead, it offers us an affect without meaning, a movement without reason, a sign that has no signified – at least, not one that corresponds to our world, which falls apart when confronted with intensive images, or is cut to pieces, if you like… The third image of fear, then, is characterised by madness. And on that note, Happy Halloween!

Works cited

BBFC, “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre”. Accessed 30/10/13. <http://www.bbfc.co.uk/case-studies/texas-chain-saw-massacre>

Clover, Carol J. (1996) Men, Women, and Chainsaws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film. London: BFI Publishing.

Deleuze, Gilles. (2008) Proust and Signs. Trans. Richard Howard. London: Continuum.

Ebert, Roger. (1974) “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre”. Accessed 30/10/13. <http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/the-texas-chain-saw-massacre-1974>

Kehr, Dave. “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre”. The Chicago Reader. Accessed 30/10/13. <http://www.chicagoreader.com/chicago/the-texas-chainsaw-massacre/Film?oid=1049921>